Japan’s peculiar Yakuza mafia magazine industry is explored in this year’s XCity. For XCity Plus, Marigold Warner and Tim Gunn present the story of its short-lived equivalent in the US: Mobster Times.

“For us, it’s an angle. It’s not a passion: it’s a way to make money,” says Frank DiMatteo, a former mafioso and the current publisher of yearly magazine Mob Candy. “I put things out because people like them and they pay me for it.”

DiMatteo grew up in New York’s Gallo crime family. In 1971, the Gallos shook hands on a deal with publisher-pornographer Al Goldstein to distribute Screw, his pioneering sex paper. The mob didn’t choose Goldstein (who DiMatteo describes as an “arrogant asshole”) and Goldstein didn’t particularly want to get involved with the mob either, but, as DiMatteo explains, “eventually, in any walk of life, people have to turn to the mob to keep going, and we help them”.

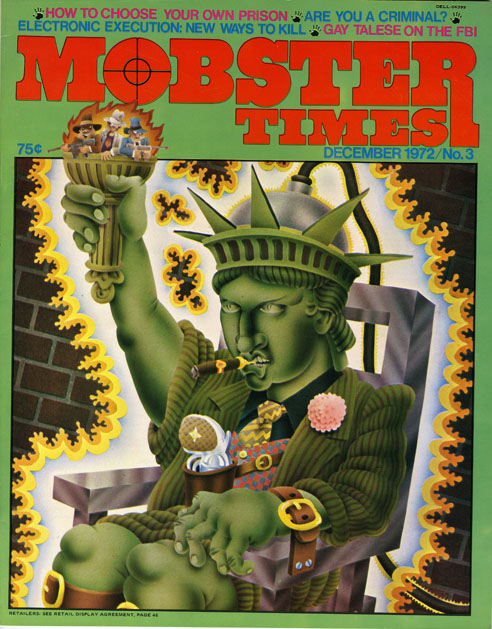

Working alongside Goldstein was Screw’s art director, Steven Heller, who went on to design the New York Times Book Review and become one of America’s most esteemed graphic designers. Together, the “asshole” pornographer, the artistic prodigy, and their gangster delivery service tried, and failed, to hip 1970s New York’s underground to something completely new: Mobster Times.

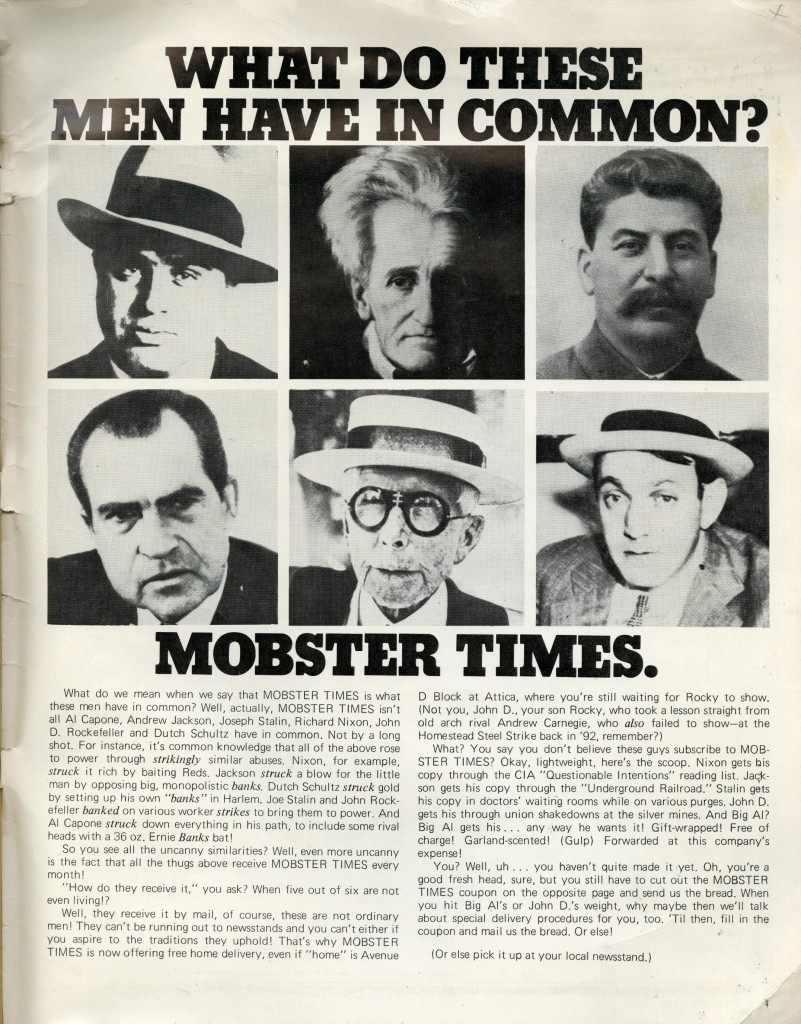

As Heller recalls: “It was a way of looking at crime from the political viewpoint, from the actual larceny of crime, but also its Robin Hood quality.” To do so, Goldstein needed a platform separate from Screw. As DiMatteo puts it, “you didn’t want to find Nixon where you expected to see two girls f***ing”.

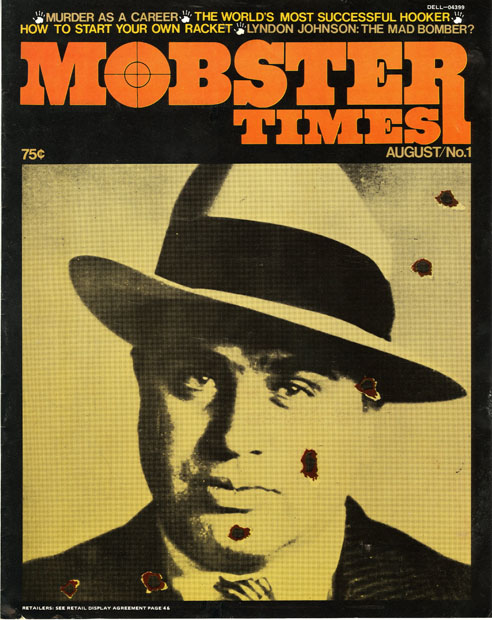

Unfortunately, the project was doomed from the start. Screw’s mafia printer was so shocked by the “commie crap” he almost refused to let it touch his presses. After some negotiation, he agreed to print it – at night. Only one printer worked the night shift, and it was dark, so the first issue’s glossy black cover, which pictured Al Capone riddled with bullet holes, came out in a dull grey. They agreed to reprint free of charge, but the delay meant the magazine came out two weeks late.

If that wasn’t enough, one particular spread sealed the magazine’s fate. On the right-hand page was the headline “the greatest criminals of all time”, inviting readers to piece together a face from the mouth, eyes, nose and ears of various tyrants and lawbreakers. On the left-hand page the pieces came together to make the face of J Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI. Unhelpfully, Hoover died the weekend before that issue was released. Mobster Times didn’t make it to newsstands that week, or any week after.

Although the magazine published writers as distinguished as Gay Talese (who later helped Heller navigate the inner workings of The New York Times), and even included a review of The Godfather by infamous mob hitman Joey Gallo (Frank DiMatteo’s uncle), it only survived for three issues. “Goldstein got bored easy,” remembers DiMatteo. “If it didn’t jump out of the gate pretty fast, he’d drop it and move on to something else.”

Despite that, the Gallos kept distributing for Goldstein for over 30 years, until changing laws and the rise of the internet ended his run as the king of New York’s underground press. “He was in bad shape at the end,” recalls DiMatteo. “He’d wasted all his money, he’d had three or four divorces, he was suffering from diabetes and he seemed delusional. He called us over to speak with him. We found him ranting and raving and dribbling on himself, demanding money from us to continue distributing. We just looked at him and turned away. We turned around and walked out of the office, and that was the last time we ever spoke to him.”

DiMatteo adds: “He was creative in certain ways, but he was dumb as a f*** in other ways, and that was his downfall. It’s an American story: from rags to riches and back to rags. But no-one else did this to him, he did it to himself.”