As XCity reaches the ripe old age of 30, we thought we would delve into the magazine archives and republish some of the magazine’s finest content. Warning: words and images may provoke severe nostalgia for the past.

Here’s our first installment, where Andrew Johnson, now assistant news editor at The Independent, tells us not to make too much of a fuss about this whole ‘internet’ thing…

_____________________________________________________________

Exploring cyber space by Andrew Johnson @andyjey (1994 – when XCity was called Newsletter)

Skipping the light fantastic: multi-media highways are predicted to bypass the printed word but many technophobes are forecasting heavy delays on the road to nowhere

Hold tight. The multi-media revolution is coming. Maybe. In case you hadn’t heard, a glittering new technological epoch of digital superhighways, cyber-space and information unlimited is almost here.

Cyberspace is the intangible place on the airwave where your telephone conversation takes place. If the pundits are right there’s going to be a lot of it about. Digital technology has made it possible for a strand of fibre optic – a glass cable as thin as a human hair – to carry the equivalent of every radio frequency put together, a thousand times over.

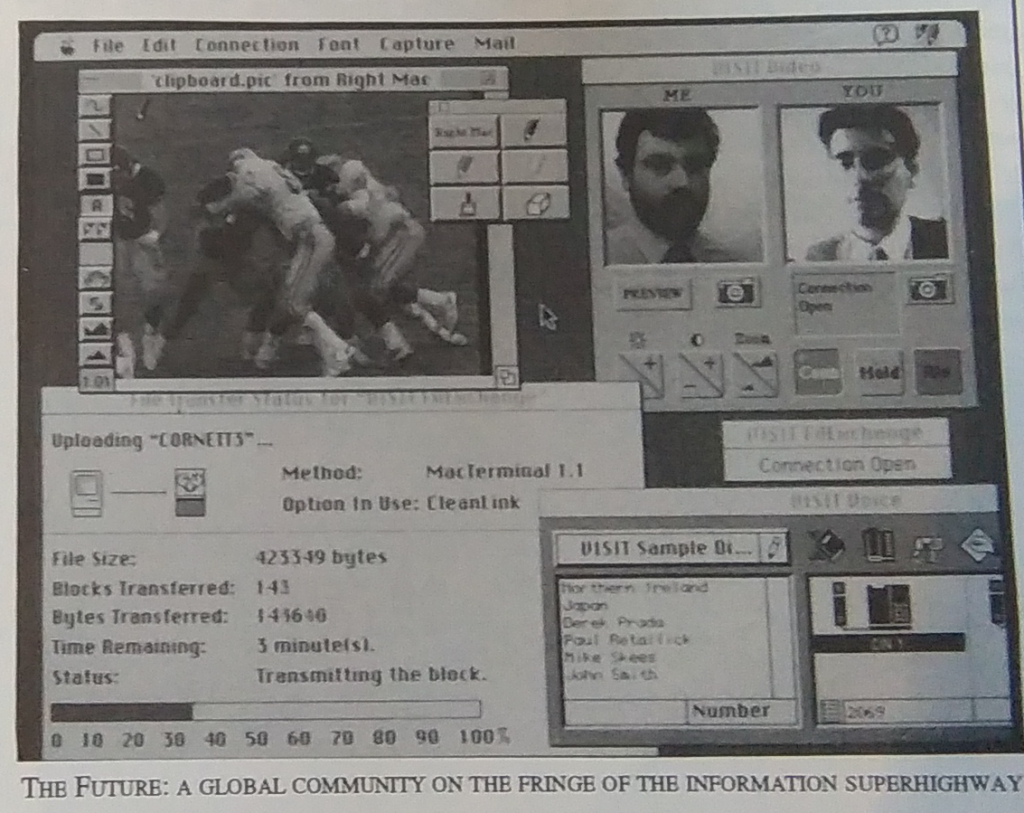

For visionaries the possibilities are infinite. If every home across the country were connected to an optical fibre highway an upheaval akin to the arrival of steam would occur. Five hundred TV channels could be carried on one fibre, both ways. Interactive TV means watching what you want, when you want. All you would need is a telephone, TV set and computer. You could dial a movie – any movie. Shop from your TV screen, dial a book, a newspaper or pick up your post from a computer terminal. You could even tune into a philosophy lecture at the Sorbonne via a video camera hooked up to the digital grid.

Media companies have quickly latched onto this potential. Unable to go it alone each has been sticking their fingers in the others’ pie. The US cable company, Viacom, recently merged with the Blockbuster video chain in order to bid for Paramount films. Nynex, a Baby Bell telephone company, recently invested $1.2bn in Viacom. Computer companies such as Apple and IBM are working together and software companies are working overtime.

Oracle, the third biggest software producer, recently announced its new “Media Server” which will manage information coming into the home. Oracle is also working with numerous companies to develop a superhighway information system, including the computer firm General Instrument and The Washington Post – to develop electronic publishing.

This activity is led by a fear of being left behind and to spread costs. Multimedia is a long, futuristic, expensive shot. The largest ever corporate merger between Bell Atlantic and TeleCommunications (TCI), was called off 72 hours before its consummation in February. The failure of the $33 bn deal was blamed on US media regulation. But independent analysts hold falling share prices to blame. Investors in both companies feared that multimedia potential did not justify the cost.

Herein lies the rub. Although the technology is there, it is obstructed by government legislation in America and in Europe, and by the inability to predict whether the public needs or wants it.

In Britain only British Telecom is big enough to create a superhighway. It is already planning a video-on-demand service, with help from the Oracle Media Server. This entails sending video films, computer games, home shopping and banking services down existing copper wires. However, BT are prevented from carrying entertainment services until 1998. Although they are already investing in fibre networks for major telephone routes and business customers, the restriction makes it unviable for them to link each home to a digital grid. Even if they succeed in having the rule relaxed, and they are lobbying hard, the restriction could still last until 2001; it would then take “several years” to connect all their 20 million customers.

Al Gore, now US vice-president, coined the term “superhighway” in 1979. He sees it as an essential piece of American infrastructure. But his government cannot afford the estimated $50bn construction bill. Again, most cities are connected but links to individual homes are missing. The cable and telephone companies could construct it between them, but they are barred from invading each other’s markets. The jostling for market position suggests they are optimistic about de-regulation, but the machinery of government is slow. Hence the confusion and uncertainty.

If the information age does arrive it will not be for at least two decades. But does the public want it? Barry Diller, the man who helped turn Murdoch’s Fox into America’s fourth national TV station joined the home shopping company QVC (Quality, Value, Convenience) in 1992. He believes there will be “a true and radical revolution of basic habits.”

QVC was launched in Britain in September 1993, via the 14 channel multi-package on BSkyB. They have no figures for consumers, able only to claim access to 3 million satellite-owning homes. There is little doubt it is big in America, turning over $1bn in 1992. Available to over 44 million US homes it hardly spells the end of the shopping mall. It is currently profitable mail order company.

Past information links show little promise. Prodigy, a $1bn national digital network created by Sears and IBM, allowed consumers to shop and bank via a personal computer. It failed because users set up chat lines instead. InterNet, a computer network with 15 million users using a conventional modem and computer, is little more than an international notice board for swapping ideas. Teletext has been available in this country since the mid 70s, but this is only used by 50 per cent of the population.

Geoffrey Mulgan used to work at the Centre for Communications and Information at Westminster University, and has written extensively about communications. He says that technosceptics are usually proved wrong in the long run but points out that “the future is wildly over-hyped, the vision tends to be misleading and wildly over-optimistic.”

And that’s the problem. Predicting the future has never been a reliable science. Perhaps it is too early to get excited.