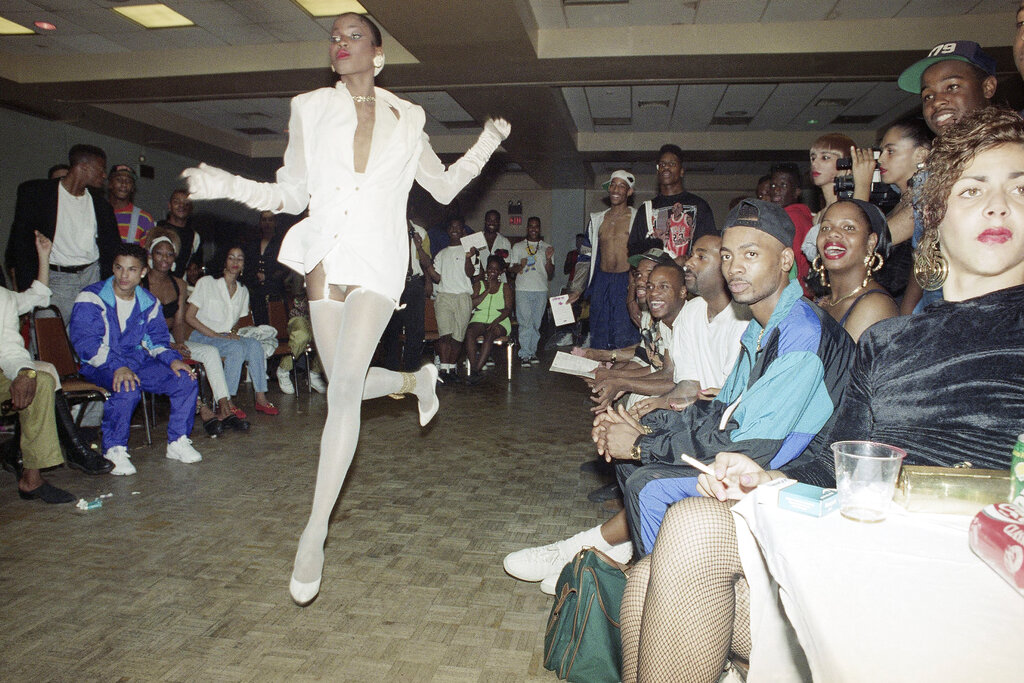

Image:(AP Photo/Andrew Savulich)

Simone Fraser looks back on the groundbreaking documentary Paris Is Burning and its lasting impact on the LGBTQI+ community 30 years after its release.

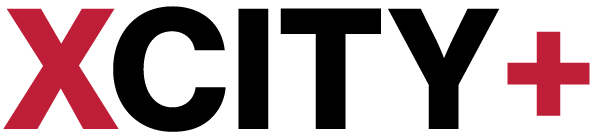

It’s 1987, the streets of New York City are pitch-black and still, but inside the packed venue of Paris Dupree’s annual ball, the world couldn’t be more different. Multicoloured lights illuminate a room crammed with dancing figures as synth-heavy 80s music pulsates. The dancers are clad in feathers, sequins, and outrageous make-up. Here, gender is subverted and rewritten. This is the opening scene of pioneering LGBTQI+ documentary Paris Is Burning.

On the 30th anniversary of its release to cinemas, Jennie Livingston’s Paris Is Burning continues to inspire LGBTQI+ youth across the world. The dazzling documentary shows the underground world of drag queens and their social scene, including its elaborate balls and diverse communities. In a world where voices of gender-nonconforming people continue to be threatened, journalists of all sexualities can learn from the candidness of Livingston’s work.

“Filmed predominantly in Harlem, New York City, the film illuminates the vibrant scene of drag balls”

LGBTQI+ representation in TV and film is crucial to helping members of the community feel more comfortable with themselves. Today, drag has become more mainstream, in a large part due to the popular reality show RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009 –) and fictionalised drag series Pose (2018 – 2021). Recent Channel 4 series It’s A Sin (2021) explored a fictionalised world of gay men in London between 1981 and 1991 – a similar period to Paris Is Burning. The show led to a huge surge in HIV testing in the UK.

However, Paris Is Burning remains one of the few snapshots into the real-life characters that populated this era. Each of the characters are real people, and the lives they live, however wild and subversive, are genuine.

Filmed largely in Harlem, New York City, the film illuminates the vibrant scene of drag balls – a world of predominantly gay men and transgender women, but inclusive of those across the LGBTQI+ community who struggled to find acceptance in the wider world.

Same-sex sexual activity was only legalised across America in 2003 after a Supreme Court ruling – until then, it was still illegal in 14 states. In the late 1980s, when Paris Is Burning was filmed, instances of ‘queer-bashing’, murders, and violence towards LGBTQI+ people were common – particularly among those who were gender-nonconforming. The film was pioneering because it gave a voice to a community of people whose existence had long been condemned and repressed by mainstream media.

Paris Is Burning has gone on to win a wide range of awards over the years, including Grand Jury Prize Documentary at Sundance Film Festival in 1991 and Outstanding Film (Documentary) at the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) Media Awards in 1992. It was added to the National Film Registry in 2016 – a collection of films believed to be worthy of preserving.

“I always felt like I couldn’t be glamorous, beautiful, and elegant. Drag changed that”

Although this film is 30 years old, it continues to inspire younger drag performers. Velvet Caveat, 22, has been a drag performer for nearly three years. She describes her performance style as “very glamorous and showy” and “inspired by cabaret, ballroom, and fashion” – concepts at the centre of Paris Is Burning. She said that the documentary, and drag more generally, have had an important impact on how she feels about herself.

She explains: “The whole idea of ballrooms and realness [convincingly portraying your drag persona] really holds true to me, especially as someone who has never felt like they fit in or felt comfortable with the labels they were given growing up. I always felt like I couldn’t be glamorous, beautiful, and elegant. Drag changed that.

“It’s about people finding a community because they don’t feel a part of society, and that’s something I relate to. It takes a lot of strength and resilience to be authentic to yourself. I hope I can help keep those kinds of spaces alive.”

Yet Caveat also sees Paris Is Burning as important because it shows dangers that persist in the modern day: “It’s such an important and authentic snapshot of hidden queer culture. The same culture that so many people tried to deny the existence of. It’s an important reminder of both how far we’ve come and also what we still need to do. Black and trans folks still suffer immensely.

“We still don’t see queer culture reflected in cinema and media often enough, much less the people of colour and low-income communities Paris Is Burning showed us so unflinchingly”

“I wouldn’t say it makes me feel more comfortable, because it’s still dangerous to be queer and radical. The documentary really shows that. Though it does make me want to be even bigger and take up more space.”

Paris Is Burning is packed with big personalities: Drag legend Paris Dupree, whose annual ball inspired the documentary’s name, Willi Ninja who was known as the ‘godfather of vogueing’ – a stylised dance style that involves striking exaggerated modelling poses and was popular in the drag ball scene – and, tragically, performer Venus Xtravaganza, who was found murdered at 23 when Paris Is Burning filming was ongoing. The killer has never been found.

The film, in part, explores Xtravaganza’s struggles as a trans woman, including a particularly pertinent scene where she describes narrowly escaping violence after a man discovered she was trans during a sexual encounter. While the documentary honestly portrays the struggles of LGBTQI+ people, it also casts a bright light on the community.

Chloe J*, 22, is a comedian and performer who identifies as bisexual. To her, Paris Is Burning remains an important documentary 30 years on for several reasons.

“We still don’t see queer culture reflected in cinema and media often enough, much less the people of colour and low-income communities Paris Is Burning showed us so unflinchingly. Paris Is Burning shows gays from underrepresented groups as part of a queer community not defined by proximity to straights.

“The documentary made me angry too. Angry that these bright, creative people, making a space for themselves in a hostile homophobic world, were in so much danger”

“Seeing communities of queer people living and thriving and creating made me feel like I was part of a lineage, even at times when I was isolated from other people like me. That said, my feelings were more complex – as a white cis gay I know there are layers to the representation of community that aren’t mine to claim.”

Like Caveat, Chloe J sees Paris Is Burning as important because it highlights the dangers that come with being LGBQTI+ in a hostile society:

“It speaks to how far we’ve come, but also how far we still need to go – the harrowing dangers trans women, particularly those of colour, for example, experience in ‘PIB’ are still hauntingly relevant now. Jennie Livingston being a queer director too, really cemented the way that the documentary was not making ‘other’, making spectacle out of queerness and gay culture.

“The documentary made me angry too. Angry that these bright, creative people, making a space for themselves in a hostile homophobic world, were in so much danger. The murder of Venus Xtravaganza, and the dangers inherent to queer culture forced to be underground filled me with an anger and a need to try and help change things.”

Joe Drakeley, 21, identifies as a cisgender gay man. Although he hasn’t tried drag, Paris Is Burning has helped him to feel more comfortable expressing his queerness in other ways such as wearing eyeliner and nail varnish.

“Paris Is Burning and RuPaul’s Drag Race helped me to feel super comfortable in who I am. Not just as a gay man, but someone who is not straight acting and is very proud to be queer. It made me realise how cool it is, because you are subversive in society still and these people didn’t care that they were different. You can’t watch it as a queer person and not be influenced by that,” he says. “It helped me realise that I’m different in a way that’s good.”

“They were living through really dangerous times – I think the majority of the people in the documentary have died from the AIDs epidemic”

The persistent threat of violence was not the only danger facing the LGBTQI+ in the 1980s. Diseases like AIDs ravaged the queer community, and many dealt with societal exclusion and extreme poverty.

Drakeley sees their perseverance in the face of such danger as one of the moving aspects of the documentary: “They were living through really dangerous times – I think the majority of the people in the documentary have died from the AIDs epidemic – and they were still so vibrant and strong. They’re inspirational.”

*Full name not provided at request of interviewee