XCity Plus asked six City international journalism alumni about where global journalism is going and how the trade works in the countries they’re based in. From risking arrest as an illegal journalist in Zimbabwe, to investigating dead bodies in Cambodia. From facing a system crash while presenting Norway’s national election, to interviewing the inventor of the internet in Egypt – they’ve all got stories to tell.

Read more below, and find the infographic with the stats of where our alumni ended up in this year’s XCity.

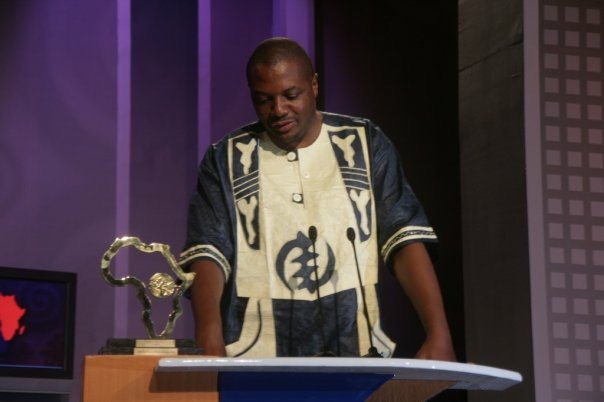

Hopewell Chin’ono, Zimbabwe, is a foreign correspondent for The New York Times and ITV in Zimbabwe, (International 2002)

Hopewell Chin’ono studied at City in 2002 and returned to his native Zimbabwe the following year, which was a time when foreign journalists were banned in the country.

In Zimbabwe, you can’t be a reporter unless you are accredited by the government. “If you go on the street with a camera and you’re not accredited, you are immediately arrested,” explains Chin’ono. In 2008, Chin’ono was denied accreditation, but he defied the government’s decision and covered the elections that year anyway. He received a police notice asking him to come to the station for an interrogation, but didn’t show up. He got away with it because he had become too prominent, having already won the 2008 African Journalist of the Year Award. Other journalists in Zimbabwe are not so lucky. Some are arrested or even killed, such as journalist and activist Itai Dzamara, who disappeared in 2015.

Eric Pape, US, is deputy editor for innovation at Honolulu Civil Beat (International 1996)

Eric Pape is now based in Miami, but has explored all corners of the world. He has lived in nine cities across four continents: Los Angeles, San Francisco, Santa Cruz and New York in the US; Paris, Barcelona and London in Europe; Phnom Penh, Cambodia in Asia; and Cochabamba, Bolivia in South America. His portfolio is as wide: he collaborated with The New York Times, The Guardian, Le Nouvel Observateur, Slate, NPR, Marie Claire, Foreign Policy, the Daily Beast and many others. He wrote about political murders by investigating the dead bodies of opponent politicians in Cambodia, and in Sierra Leone he showed how American hip-hop has helped people to tell their own stories about war traumas.

Covering atrocities comes with an emotional toll, but Pape is confident his work makes a difference. “I tried to change things in practical ways and… only focus on debates where there is room for changing minds. There’s no point in joining the abortion debate in the US or the Israeli-Palestinian debate, because neither side will change their minds. But through good storytelling you can make people care about things they otherwise ignore.”

He is currently investigating why Hawaii has become the most expensive place to live in America for Honolulu Civil Beat, the watchdog website set up by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar.

Signe Hotvedt, Norway, is a reporter for the Norwegian state broadcaster NRK website, in Norway (International 1990)

Signe Hotvedt, who came to City in 1990, has worked for the Norwegian state broadcaster NRK since 1986. She is now a reporter for its website, which is the second largest in the country.

Hotvedt says that, given its smaller population, Norway is “much less formal than Britain”, which eases the media’s access to people in power. There’s a system of subsidising small local newspapers to avoid media monopolies, although the recent Conservative government has been cutting them.

Her most memorable stories? “I love elections and have been lucky enough to cover all national and local elections for more than 30 years. I still get shivers though when I think of the 2005 election, during which I was responsible for the election result service on our website. At one point the whole system crashed. It took us around 20 minutes to get the service back up, and I felt sick for a week afterwards.”

Martin Stabe, Germany, is head of interactive news at Financial Times (International 1997)

Born in Germany and raised in New York City, Martin Stabe moved to Britain in 1997. He studied at City in 2005 and is now a data journalist at the Financial Times (FT).

“Only a third of the FT’s audience is based in the UK. Another third are in the US and the rest are spread across the world. We can’t write our content based on the fact that a citizen is part of a specific nation,” says Stabe. He adds that things are changing, and the media is becoming more international since the internet. “The FT was unusual in having a global distribution. That’s the norm now. You see Daily Mail posters in the New York subway. But most of the media is still very local.”

As a student, his national identity concerned him a lot. But now he just thinks of himself as an EU citizen living in the UK. “What I feel about my identity is far less important than what my legal reality is.”

Azer Sawiris, Egypt, is foreign correspondent for L’Ahram in Finland, (International 1997)

Azer Sawiris is one of the few Arab foreign correspondents in Finland. He joined City in 1997, after 10 years of reporting for Egypt’s largest newspaper and also the oldest Arabic newspaper, L’Ahram, which he still works with.

On his first day for Egypt TV in 2004, he interviewed Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the world wide web. His interview was broadcast on Finnish television channels, too.

Sawiris says: “In Egypt there is no journalism, no fact checking, no thinking about libel. I couldn’t work there after 15 years of journalism in Europe. We’ve had a political revolution there but we need a media revolution too. By working for L’Ahram, I try to spread good Finnish practices in Egypt.”

Abdi Osman, Kenya, is associate editor at Citizen TV Kenya, (International 2005)

Abdi Osman came to City straight from Kenya in 2005. He was sponsored by Sky News and did his work experience there. Now he’s back in Kenya, working for the biggest broadcaster in the country, Citizen TV Kenya, as an associate editor.

He says: “Kenya has a more vibrant media than the rest of Africa. The press is free and there is little intimidation of journalists.” One of the most exciting new developments is the launch of the first TV station in a vernacular language, not English or Swahili. NOORO, the broadcaster which only started in December last year, will work in the language, which is spoken by eight million people (22% of Kenya’s population). This is following the popularity of local radio stations broadcasting in vernacular languages.