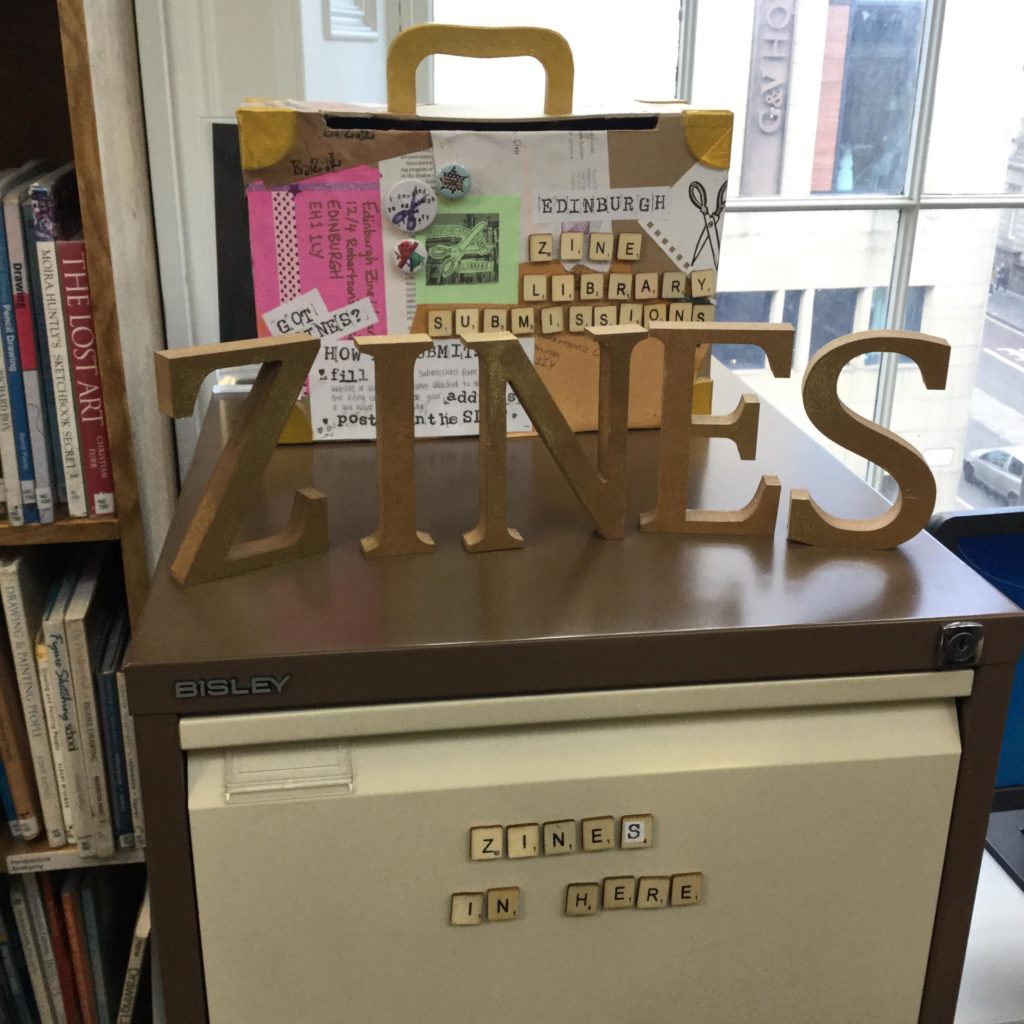

On the top floor of Edinburgh’s Central Library, an ornate building first opened in 1890, is a nondescript metal filing cabinet. Its top drawer is full of makeshift magazines, photocopied and stapled together. Across the pages are handwritten texts and drawings that cover the poetry of Bruce Springsteen, radical transfeminism and practical guides to hosting sex parties in your house (with helpful illustrations). This is Edinburgh Zine Library, one of many new initiatives across the UK which is bringing a doggedly alternative form of publication to a wider audience.

Zines have covered leftfield culture since they began.They get their name from fanzines, which were produced in the 1930s for communities of sci-fi lovers. When photocopiers became more widely available in the late 20th century, young arty types responded to the punk scene in 1970s New York or the Riot Grrrl feminist movement in the 1990s with their own DIY publications, full of art and text that engaged with the boldest ideas in culture and society. Anyone could make and distribute an utterly uncensored zine, making each paper bundle a powerful symbol of creative liberation.

Today zines are more popular than ever. Major cultural institutions like the Wellcome Collection and The Tate are developing zine collections. Zine fairs, an important part of the zinester community where new zines are swapped and sold, are popping up across the country. Glasgow Zine Fest recently received funding from the Scottish government for its annual event. Online craft shop Etsy has over 20,000 different zines for sale. What gives zines their enduring popularity? And why is this most rudimentary form of print publication in fine health as all around us glossy magazines are struggling?

There is a lot of debate around the official definition of a zine. It can contain fiction and reportage, personal essays and poetry, photography, art and collage. Despite variations, it’s generally agreed that zines are DIY, self-published and not for profit. This last one is important: the term “zine” has in recent years been used as a marketing tool, a badge of alternative thinking. The $80 “zine” created by Kanye West in 2016 to advertise his new line of footwear is not a real zine.

There is no barrier of entry to creating a zine. All you need is a pen, paper and access to a photocopier. This makes them a uniquely lo-fi, democratic form of publication, while small distribution runs keep the community tight. Lilith Cooper, founder of Edinburgh Zine Library, says: “It’s very unusual to have read a significant number of zines and not to have started making zines yourself.” Zine-makers swap their new creations, contribute to each other’s publications and share tips. Each maker has total creative freedom, managing every aspect of production from first concept to printing and distribution – a level of creative control unimaginable in the professional magazine industry.

Many predicted that the rise of the blog would spell the end for zines. In fact, the internet has fuelled the zine community in unexpected ways. Zinesters use the internet to sell their work on sites like Etsy. Newcomers can watch Youtube videos to learn about zine-making. The printed page also allows for possibilities that the internet doesn’t. There is no opportunity for trolls to comment on your printed zine. More conceptual zinesters can also experiment with form and image, using collage to guide the eye around the page in non-linear fashions.

Perhaps most importantly, the final printed product that you hold in your hands in reassuringly tangible. “Print publishing means that we’re not just posting articles that get lost in the ether of the internet,” Sharan Dhaliwal, editor of the Burnt Roti zine told The Guardian. “We’re shoving our faces in everyone else’s and saying: ‘We exist.'”

The people saying “we exist” are not just independent creators. They are often members of minority communities and groups who are still underrepresented in print media. Because of the absolute creative control and cheap production costs offered by the zine format, they have become an important way to represent alternative narratives and lifestyles. Many zines focus on supporting queer narratives, people of colour and feminism.

Often these are people telling their personal stories, which is particularly important. “Lots of social movements have been rooted in the power of individual testimonies,” says Cooper. “When zines come together, particularly in a library, they form something more than personal confessional stories. They become a social history.”

This is a history made up of countless individual expressions, both artistic and personal, from people whose voices often go unheard. Right now there are more spaces than ever which store these histories for anyone to access. And they’re not just appearing, they’re growing: Edinburgh Zine Library just expanded into its second drawer of the filing cabinet.