Beneath the user-friendly surface, there is a decaying impartiality at the core of Apple News

Just three days before the 2019 general election, Apple News sent out a push notification linking to three video highlights of the Conservative campaign; Boris Johnson pocketing a reporter’s phone, Matt Hancock being heckled by activists and the party defending Priti Patel’s crime statistics mix up. Had the BBC or Sky released this embarrassing collection of footage, you may well have heard cries of foul play from Dominic Cummings and James Cleverly. But Apple News, which has 11m UK users, managed to escape criticism from both Britain’s politicians and public.

The inaccessibility of Apple editors plays a major factor in their lack of culpability. Unlike most journalists, the team do not include their job titles on their Twitter profiles and most accounts are locked on private mode. Bios instead include redolent apple symbols, suspicious side-eye emojis and simply the word “news” without organisational affiliation. After an election that saw the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg harangued for a supposed lack of impartiality, it is unsurprising the journalists would rather hide in plain sight.

Broadsheet editors who liaise with Apple regarding what content will be published to the app are similarly elusive. Abhijeet Ahluwalia, newly-appointed Apple News editor at The Times, has been told not to give comments to press about Apple News. How can the press be free when it is scared to speak of its proprietor?

It is logical for outlets to keep quiet on the topic. An anonymous social media manager at an unspecified British news site told Jim Waterson at The Guardian: “You could get a million views in the UK alone if they pick one of your stories,” and hinted that publications were addicted to the user numbers that the app directs to their content.

According to The Guardian’s source, Apple advises in-house editors on what subjects and stories the app will privilege that week, thus generating the potential to influence the editorial output of the UK’s main media organisations.

The Guardian has had a turbulent relationship with Apple News, pulling its content from the app in 2017. However, in January 2020, just months after Jim Waterson criticised the app for its impartiality, The Guardian’s content once again became available to Apple News users, suggesting even its critics cannot resist the draw of the app’s readership figures.

But who is making the app’s publishing decisions and why? Rather than allowing algorithms to pick the headlines like Google, Facebook or Twitter, Apple News has positioned itself as an antidote to fake news by hiring humans to pick the stories of the day. In London, a team of only five news editors judge the veracity of a story through analysing the trustworthiness of its publication and the credibility of the story before pushing an alert to the masses.

Whilst this human-led approach may prevent the spread of fake news, it ignores an intrinsic flaw of humanity; bias. Sander van der Linden, director of the Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab, said: “Any curation process is likely to have some biases. I doubt they have considered fully the social and psychological consequences for how people consume news. The potential influence of Apple News is huge when selecting what their users are exposed to.”

Andy Sharman (ex-Financial Times), Henry Clarke Price (ex-BBC) and Michael Rundle (ex-WIRED), the most accessible of Apple News’s UK editors, who publicly declare their positions on the networking site LinkedIn, were all approached for comment on the issue of bias but did not respond.

The concept of curation and human bias in news is not a new concern.“Bias by itself is nearly impossible to eliminate entirely,” says Cambridge online-misinformation researcher Jon Roozenbeek. “If news apps are open about being slanted to a degree in one direction or the other (e.g. The Daily Mail or The Guardian), then readers know what to expect.”

But the power of Apple News’ monthly user numbers has bred a culture of secrecy in newsrooms. It is the most used news app in the world, and if editorial decisions and consequent biases are not more transparent, this influence could have cataclysmic repercussions for the impartiality of the UK media.

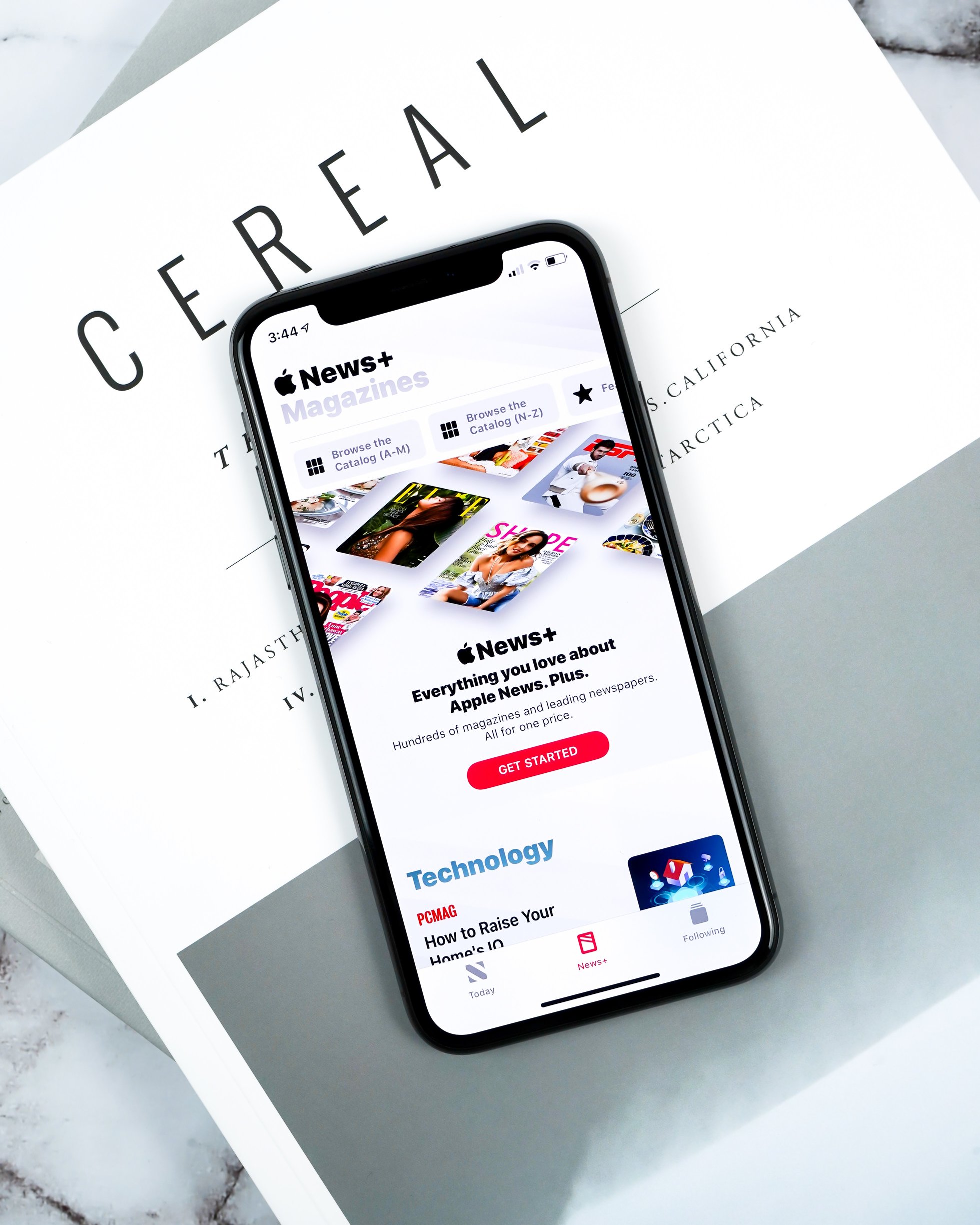

Additionally, Apple News is subtle. It is so ingrained in our existence that you might not have even noticed it lingering there in the background. Since 2015, the app has been pre-installed on Apple’s iPhones, MacBooks and their copious other products. This spoon-feeding technique has proved successful; alongside the UK’s 11m monthly users, it has 85m users globally.

This number only rises when considering those who don’t open the app but still receive its regular push notifications. These pop-ups, which slide across our screens roughly six times a day, alert us to breaking news and features from a selection of publications who allow the app to host its content. In the UK, this includes titles such as The Times, The Telegraph, The Evening Standard, The Mail, Sky News, The Mirror, The Sun, Buzzfeed, and the BBC, as well as a host of glossy mags and pop culture sites.

“It is a concern that push notifications encourage readers to only read the headlines, but one that can be compared to people only reading the front-page headlines of a newspaper,” said Jon Roozenbeek. “Headlines are the most visible part of a news item, so they’re bound to outsize influence on how a person reading a news story interprets it.”

With its direct access to a sixth of the UK population, Apple News notifications are powerful. The publications it privileges and the headlines it chooses to push, therefore, have remarkable influence over what news the country reads and from where. These notifications have enormous power to shape our understanding of sociopolitical issues and consequently our beliefs. Yet, nobody is regulating them.

In February this year, Knives Out director Rian Johnson revealed that Apple does not allow its products to be used on-screen by villainous characters. But, in the world of impartiality, it is arguable that Apple should become a symbol of surreptitiousness rather than virtue.

Want more? Check out some of XCityPlus’s other latest posts here.