At 3.00am on the morning after the Boston Marathon bombings in April 2013, Anonymous’ Twitter account @YourAnonNews tweeted the names of two bombing suspects, 20 minutes after a similar tweet from unknown Twitter user Greg Hughes.

The first name, Mike Mulugeta, had been announced on a police scanner. But the second, Sunil Tripathi, was a missing Brown student whom Twitter and Reddit users had misidentified after comparing FBI-released images of him to surveillance stills. Anonymous’ tweet was retweeted over 2,500 times.

Police on scanner identify the names of #BostonMarathon suspects in gunfight, Suspect 1: Mike Mulugeta. Suspect 2: Sunil Tripathi.

— Anonymous (@YourAnonNews) April 19, 2013

Journalists from Buzzfeed, Politico and Newsweek tweeted the same information. As word spread, Hughes (@ghughesca), the first person to tweet the two names, tweeted again: “Journalism students take note: tonight, the best reporting was crowdsourced, digital and done by bystanders.”

But Sunil Tripathi had disappeared on 16 March 2013, a month before the Boston Marathon. His family, who had been looking for him for the previous month, were suddenly subject to calls, social media posts and emails making allegations about him.

A week after the marathon, his body was pulled up from the Providence river and identified using dental records. The journalists who had tweeted Tripathi’s name deleted their posts.

Hughes – who has since disappeared from Twitter – couldn’t have been more wrong. That night was a showcase for the worst that social media is capable of: a digital witch-hunt led by amateur investigators. Spurious allegations were reported as fact.

“Like with any technology, if it’s got the potential to be used for good, it can be misappropriated.”

Of course, there are two sides to the digital coin. During the fallout of the MPs’ expenses scandal, for example, The Guardian set up a crowdsourced dataset to work through receipts provided by the House of Commons. In this case, many hands made light work of the mounds of data.

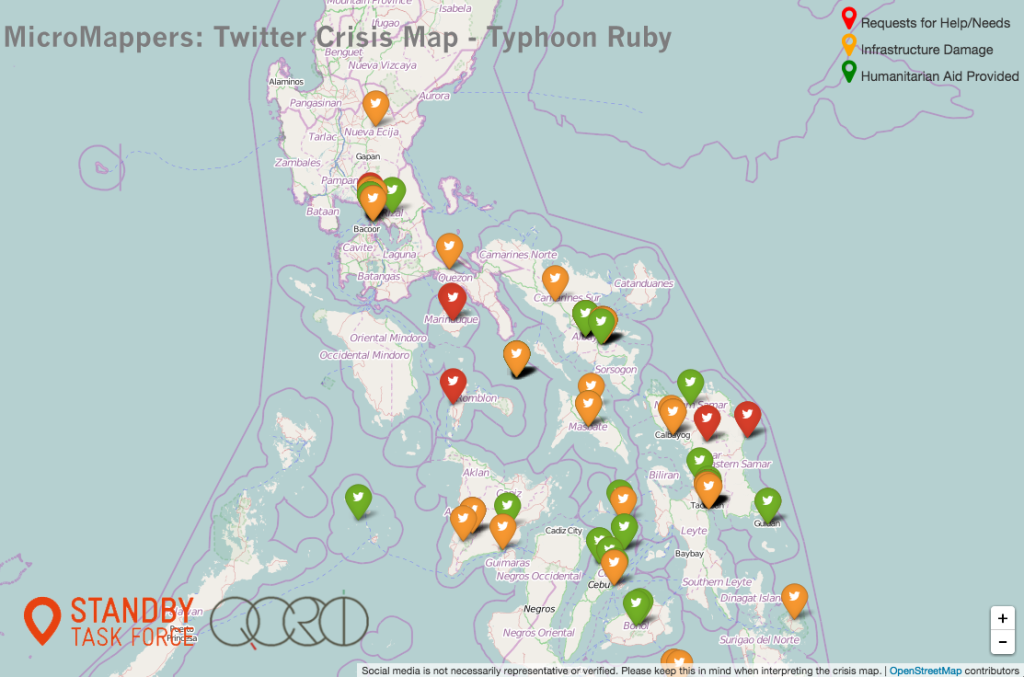

And it’s not just limited to data in the internet-led changes to news production and consumption, says Dr Neil Thurman, a researcher at City University. “There are lots of tools that allow people to collaborate. Some of those prove quite useful in crises – a hurricane or tornado – because you might still have mobile connectivity. You can map out where people are, where the survivors are, where the help is.

“But like with any technology, if it’s got the potential to be used for good, it can be misappropriated for purposes that aren’t ideal.”

The same goes for live coverage of crises. In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo shootings, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, told broadcasters that live coverage could risk hostages’ lives and cause difficulties for the police. In an age where live coverage is becoming the norm from readers, what does this mean?

“People can forget their civic responsibilities, tweeting stuff to journalists directly rather than the police.”

It’s a balancing act, says Belinda Alzner, marketing manager for ScribbleLive, the largest liveblogging platform in the world. “Journalists are balancing the public’s right to know with interests of privacy and security. It’s a delicate balance to seek, especially in a breaking news situation that can be messy at times. Journalists are using liveblogs to deliver news as they learn it.

It’s a balancing act, says Belinda Alzner, marketing manager for ScribbleLive, the largest liveblogging platform in the world. “Journalists are balancing the public’s right to know with interests of privacy and security. It’s a delicate balance to seek, especially in a breaking news situation that can be messy at times. Journalists are using liveblogs to deliver news as they learn it.

“When training users on our product, we try to highlight real-time editorial processes like staging liveblogs, or collections, where reporters can file and editors can edit before sending live.”

It’s a process that would have been useful five years ago. Dr Thurman, a leading expert on liveblogs, notes the criticism drawn by the Guardian in 2010, in their liveblog about the gunman Derrick Bird. In two hours he killed 12 people and injured 11 others in villages across Cumbria. During the manhunt, the newspaper asked readers to send information to them, but didn’t suggest they contact the police. “They were liveblogging the Cumbria shootings before he’d been caught,” he says.

“This appetite for live news, people get into that not just as observers but also as contributors; they can forget their civic responsibilities, tweeting stuff to journalists directly rather than thinking if it’s better to tell the police.”

But live coverage isn’t always dangerous, as long as precautions are taken. Virginia Fiume, ScribbleLive’s Training Specialist, says: “Creativity can allow for anyone to excel in liveblogging. Breaking news is messy, but collaboration tools allow news organisations to streamline their editorial workflows in the heat of a moment and get their reporting to the public in the timeliest manner.”

During the Charlie Hebdo tragedy, Fiume says, more than 15 European media outlets used ScribbleLive to break news to the public, reaching over 1.2 million viewers. “The coverage of the incident provided crucial live updates, helping to reduce further risk as the public was informed throughout the emergency situation.”

During the Charlie Hebdo tragedy, Fiume says, more than 15 European media outlets used ScribbleLive to break news to the public, reaching over 1.2 million viewers. “The coverage of the incident provided crucial live updates, helping to reduce further risk as the public was informed throughout the emergency situation.”

It’s still up for debate whether or not live coverage reduces risk – but according to Dr Thurman, verification is a responsibility in any live coverage: “The desire to be updated constantly either online or on TV is difficult to resist if competitors are doing it, but there are implications in terms of credibility and even public safety.

“There’s a temptation in this live environment to push the boundaries of acceptability when it comes to verification.” And in the tragic case of Sunil Tripathi, that’s not a risk worth taking.