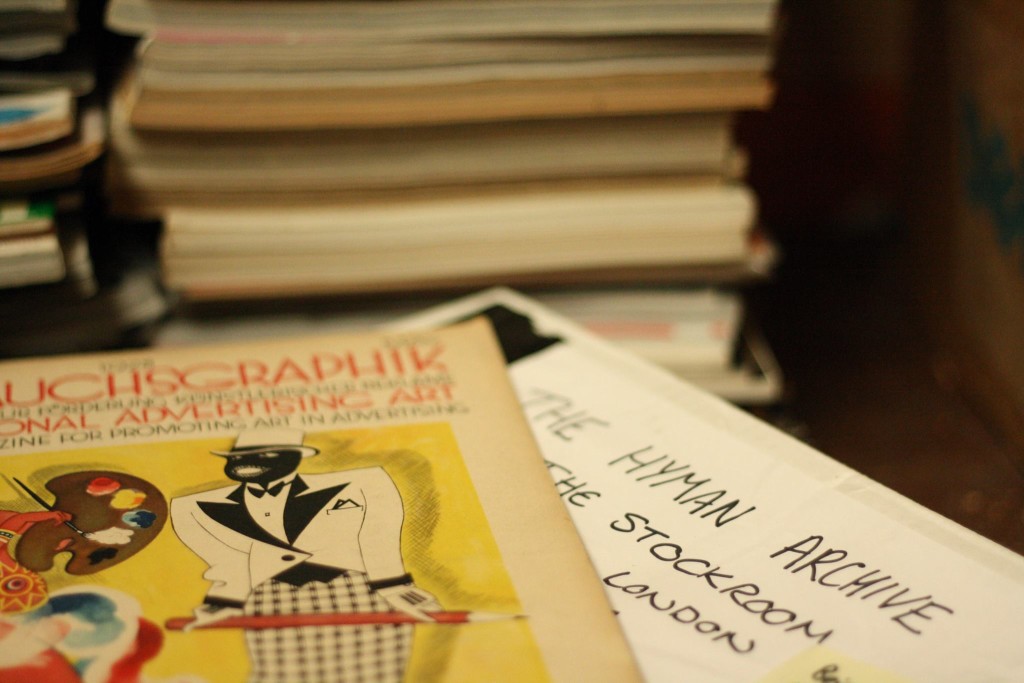

We pass by two iron cannons as we go through the main door of Cannon House, a 19th century storehouse in Woolwich Arsenal and home to the world’s largest magazine collection: The Hyman Archive.

The Hyman Archive is home to 70,000 issues and 3,000 titles, outnumbers the British Library archive by 55 per cent and won owner James Hyman his Guinness World Record in 2012.

Everything’s there, from the 1910s catalogue of the German record company Deutsche Grammophon to the first ever Playboy from 1953 showing rising cover star Marilyn Monroe giving an inaugural wave.

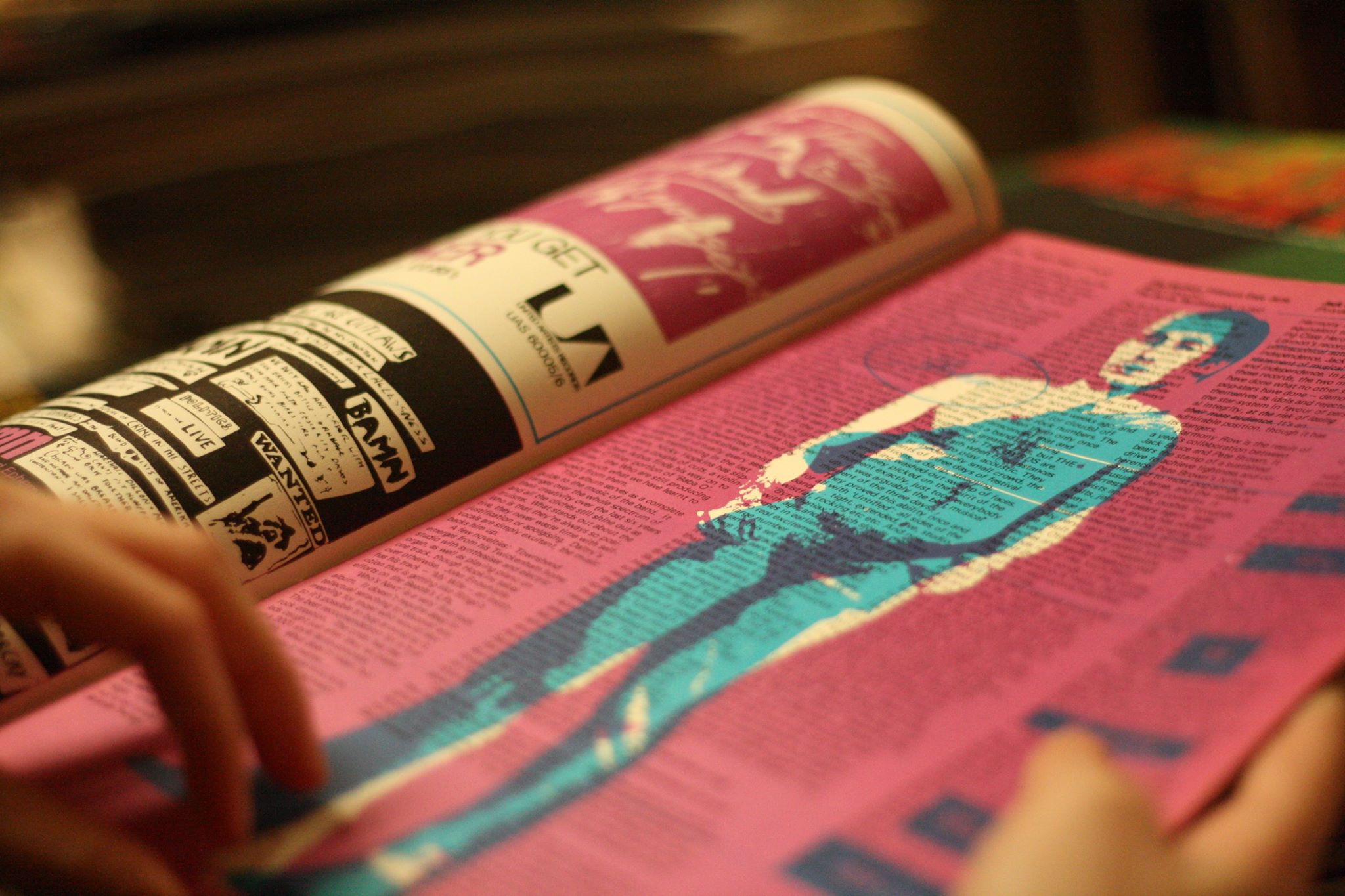

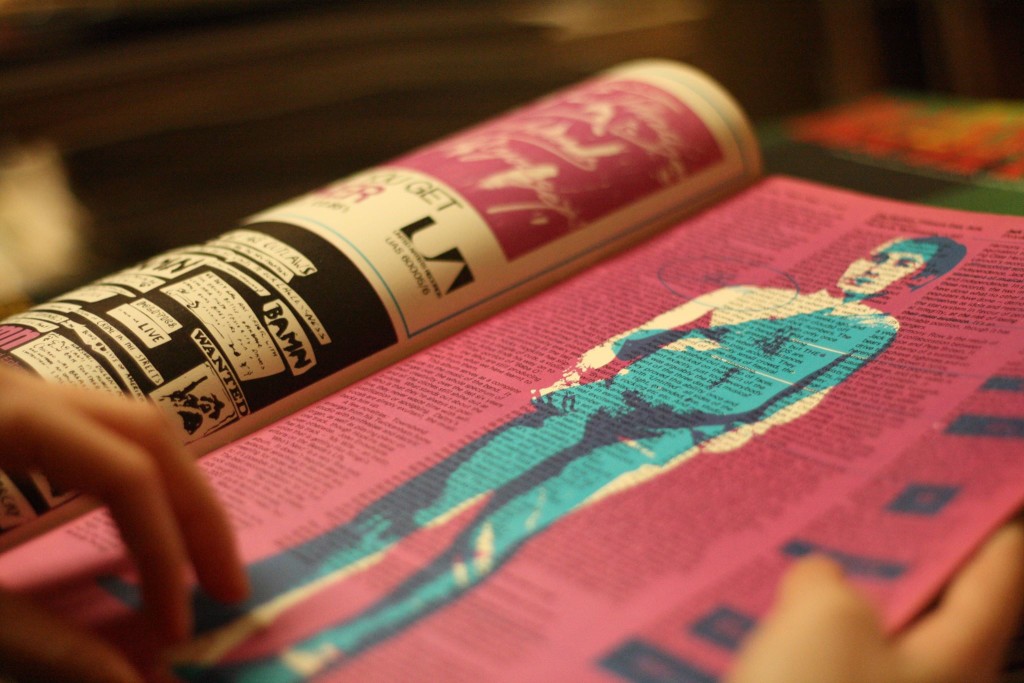

The magazines reflect history with a small h: they’re snippets of contemporary daily life. 1980s NMEs track the rise of acid house, whilst Dazed issues from the early 1990s shout freedom and coolness beside the glossy, glam Harrods issues of the 2000s. This is an archive of zeitgeists.

We flick through a 1970s issue of the countercultural magazine Oz. Hyman notices a picture that reminds him of Tarantino’s debut film Reservoir Dogs. He started reading magazines in his teens. Smash Hits, NME and Jocks were all ways to see the celebrities he found on American TV and read about the video games that were just coming out. “I don’t think I’m unique,” Hyman says unassumingly. “Everyone loved radio, TV, magazines, pop culture.”

By 1990, as a scriptwriter at MTV Europe, Hyman had begun his collection. “Magazines were the internet then,” he says, so they became the source material for the presenters’ commentary between videos of Madonna, Prince and other stars of the day. It was also then that Hyman started his record collection, which peaked at 50,000. Before his two children were about to be born, Hyman’s wife told him to “clear some of this stuff out”. He gave in and tells me their house now looks “respectable”, holding only a modest 30,000 CDs and 5,000 DVDs. But the Hyman Archive allows his drive for magazine collecting to run free. Hyman’s favourite magazines today range from Vanity Fair, The New Yorker and The Wire to 2600 Magazine – a title that focuses on surveillance and, aptly, started in 1984 – and which featured stories on hacking and digital underground figures such as internet drug lords. He also loves looking through indie magazines as “products of passion”.

One of Hyman’s latest acquisitions is a set of 113 issues of the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, which he got from a bookshop in Notting Hill. The magazine, brought to the store by the Metropolitan Police, covered the police recordings of JFK’s assassination, and had images of policemen with kids, saying: “Hey, kids, grow up and be good.”

As we walk down aisles of six foot shelves, Hyman asks Tory Turk, the collection’s archivist and a fashion curator, to help him find a 1928 German magazine with incredible design. “Right there, by that stack. Is that it? Please be the one,” Hyman begs. The scene repeats a couple of times over the hour.

Every time it happens Hyman consoles himself with the idea that once the archive is digitised – scanned and tagged – it will be much easier to find everything. “Say you’re looking for articles on Prince, or a specific issue of Life magazine, or you’re writing about sexuality in Oz, or if you wonder: ‘Hey, what did Miami look like in the 70s and 80s?’, it will be much easier when the back issues are available online.” Before the collection reached the current Cannon House stockroom in 2015, it was spread between private homes and a smaller Islington warehouse. Digitisation is the next step, but Hyman still intends to maintain the physical issues for public use.

At the moment the Hyman Archive is available by appointment only. One lady wanted to use an article from GQ as evidence for the police to issue a warrant on a fraudster. The trial is now on. There are nostalgic requests too. Barry McIlheney, Chief Executive of the Professional Publishers Association, wanted to see the letters he wrote to NME in the 70s. Hyman retells: “He even said himself ‘What the hell was I writing?'” Jeremy Leslie, the man behind the Magculture studio, stayed for hours to just look at the older magazine designs. Hyman loves sharing his archive: “I’ve always wanted to share my passion and interesting content, whatever the medium: DJaying, radio, TV, film soundtracks and here via print.”

Will we only lose pretty objects once our material culture shrinks for the digital? Hyman voices the usual critique of the online: “The internet now in so many ways is not always the truth. It lies. With a magazine, you have the responsibility to get things right.”

Nevertheless, digitising the archive will help Hyman spread the spirit of in-depth, well-researched stories to the online realm, and perhaps change it.