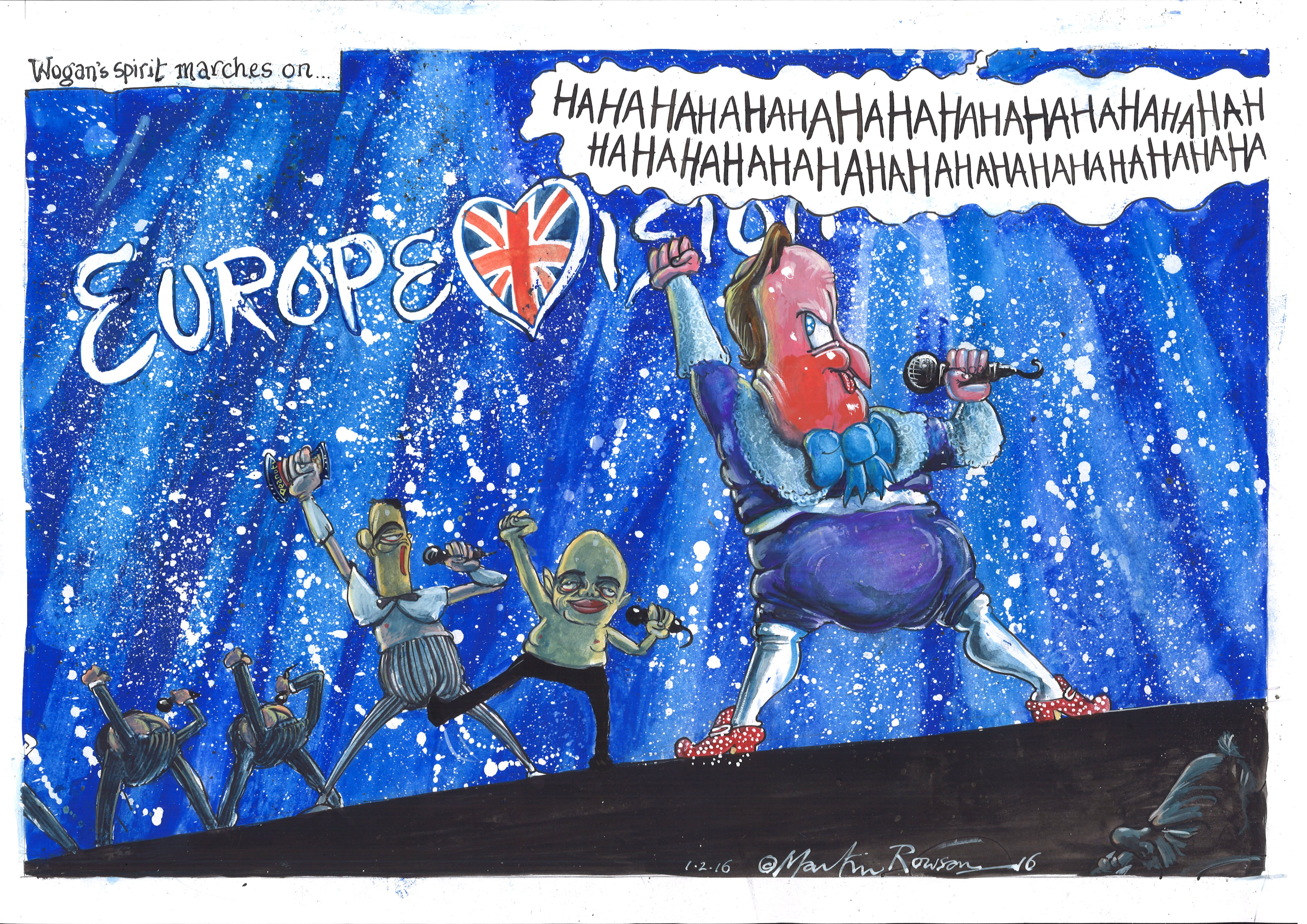

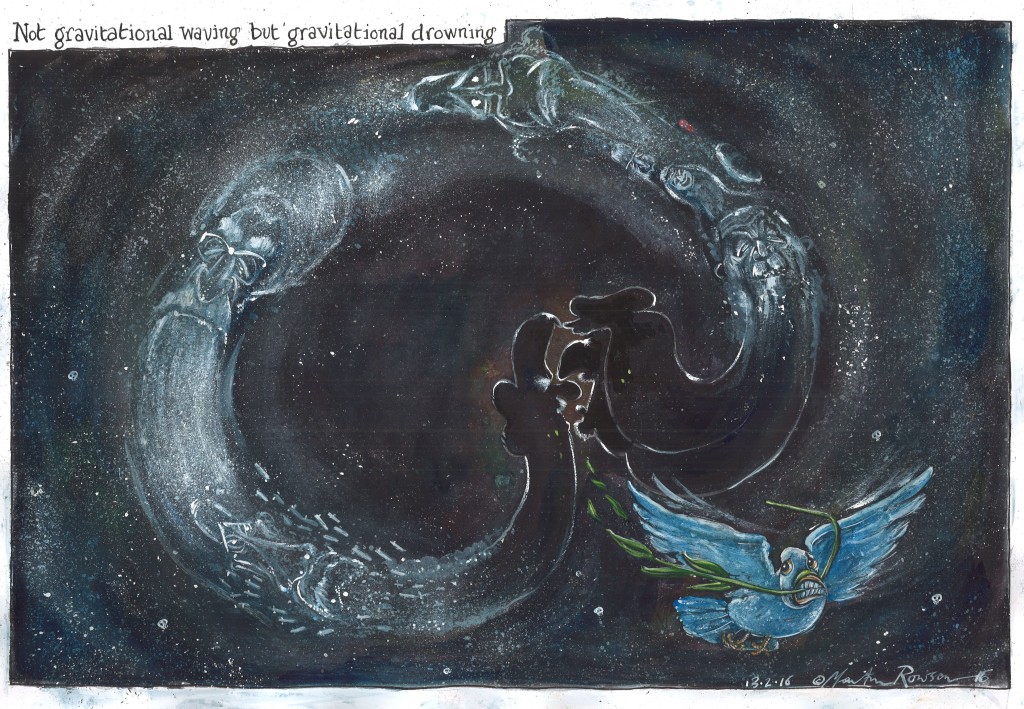

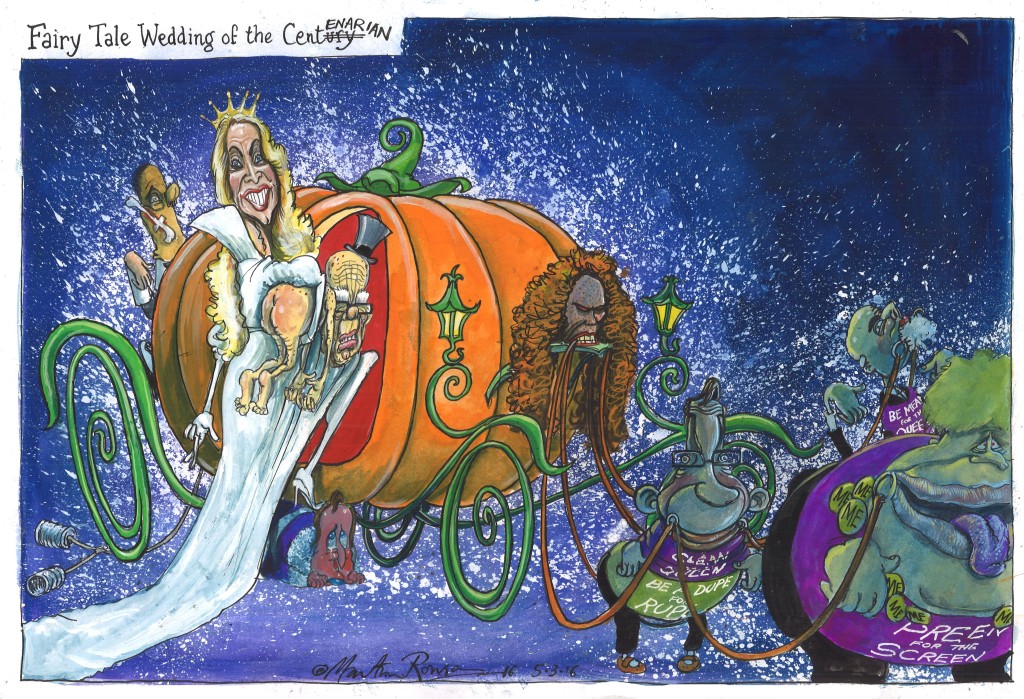

Martin Rowson is a multi-award-winning cartoonist whose work has appeared in every daily national newspaper. He talks to Celia Lloyd-Jones about the politics, pressure and processes involved in his trade.

“Cartoonists are always the first to be sacked,” declares Rowson, cartoonist for The Guardian. “I can’t think why it wouldn’t be the gardening or the fashion sections, because they’re such a load of rubbish. Cartoons are an integral part of a newspaper. But then I would say that, wouldn’t I?”

Rowson sees his trade as akin to a kind of visual journalism, through which he tries to put the powerful and influential firmly back in their boxes. “I go for the obvious joke,” he says. “People often say: ‘Why are you always so negative?’ But why the hell shouldn’t I be? I see nothing wrong with being entirely oppositional. People ask me: ‘What do you think about Syria?’ But my thoughts on Syria are similar to that of a small, frightened dog. All I do is comment on the news with a visual allegory that is funny.”

“But it is serious,” he hastens to add. “What my colleagues and I do is deadly serious. A great deal of thought goes into our work. Many of our jokes come from anger and disgust – that’s a power we have over politicians. Never underestimate the power of being able to laugh at the f**kers. He hates it,” – he gestures to today’s cartoon of Boris Johnson – “which is why he tries to make fun of himself.”

Rowson admits he is the only cartoonist he knows that reads people’s comments below his work. “You can’t draw,” said one today. “Well, clearly I can,” he retorts, “they just don’t like the cartoon. It’s interesting because I never hear of people telling writers they can’t write.” And like writers for a daily paper, Rowson’s cartoons have to reflect the news every day. “We don’t have back up cartoons; this is journalism so it has to be fresh and current. Sometimes people don’t believe me when I say there’s no news. But of course, even if there’s no news, you find something.” He glances at today’s cartoon about Boris’ decision on the EU. “I got that idea after listening to the 12pm news yesterday. I started at 4pm and sent it off at 6pm.”

How much editorial control does The Guardian have on his work? “There are two of us – Steve Bell and I. Steve is more gung ho than I am and rarely consults the editors, whereas I usually outline my intentions to avoid clashes with the column below. Obviously we have to consider what our readers can stomach, but we complement each other quite well, because our styles are very different.

“But we are lucky at The Guardian. I have been known to resign where I’ve had less freedom in my work. I remember one particular conflict with one of my editors over the Iraq war – I was against it and he was for it. Every Friday his deputy and I would have the battle of Stalingrad, which resulted in me saying: ‘If the editor has such good ideas, can I recommend that he learns how to draw.’”

It is a skill that Rowson taught himself. “I have absolutely no training,” he declares. “When I saw some war cartoons in my sister’s history textbook at the age of 10, I knew I wanted to be a cartoonist. I started copying other cartoons and had my first one published in the New Statesman when I was reading English at Cambridge.

“I often discover new techniques and my style has changed dramatically over the years,” he says. “I used to work in black and white but when colour presses were invented in the mid-nineties, I had to teach myself how to paint again. I prefer working in black and white because I love the techniques involved, such as cross-hatching, but colour takes much less time to achieve the desired effect. I work on Bristol paper, using Indian ink for the outlines and gouache paint for everything else.”

And it’s not just Rowson’s technique that has changed over the years, but the way he depicts his subjects, too. “Blair’s face has changed completely,” he says. “If you look back to my early drawings he was almost puppy-like. He’s become haggard over the years, his teeth and ears becoming more and more exaggerated. You need these prominent features to cling on to. People with subtle features are difficult. I know many cartoonists who have struggled with Nick Clegg, for example.”

And what if someone has the same idea? “It’s an unwritten rule that when one of us has a good idea, like Steve’s brilliant one about likening George Bush to a monkey, we’ll let him have it. We’re quite decent in that way.” And with an uproarious laugh, Rowson gets back to his drawing board.