The BBC’s recent adaptation of The Trial of Christine Keeler shows how little has changed in the media’s treatment of women

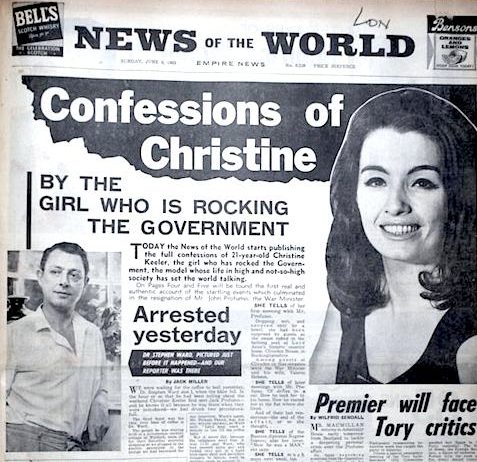

Nearly 60 years after the Profumo Affair, the inferno surrounding Christine Keeler has refused to die down. For over half a century she has remained the “devastating, leggy beauty” who, aged only 19, slept with the secretary of state for war and – in the ensuing controversy – brought down a government.

Yet, this year has seen a radical reimagining of her traditional femme fatale narrative. BBC One’s recent six-part series, The Trial of Christine Keeler, has, for the first time, offered an adaptation of the story through the “female gaze”. Post-#MeToo, it seems an appropriate time to revisit the case, but how much has actually changed?

Traditionally-speaking, Keeler – as much as the Profumo Affair that made her name – has remained entrenched in the glamour and scandal of the 1960s. Her autobiography, Secrets and Lies, was published to salacious acclaim, including one panting reviewer who branded her an “icon of the ditzy sixties”.

However, beneath the glitz and the gossip, at its root, Keeler’s story was one of a teenage girl who was abused, exploited, and ultimately discarded by a powerful male elite. There were her lovers, John Profumo, the 46-year-old secretary of state for war, and Yevgeny Ivanov, the Soviet spy, whose love triangle brought ruin upon Harold Macmillan’s government in 1963. There was her alleged best friend, Stephen Ward, who used her as a honeytrap to extend his own influence. And, ultimately, there was a bloodthirsty media who hounded and ridiculed her until her death in 2017.

While Profumo’s reputation recovered to a level that saw him honoured with a CBE in 1975, Keeler’s never did. She was sexualised by leering tabloid paparazzi until she reached an age where she was no longer saleable. Over the decades, her story became one not only of a chauvinistic elite, but of a naive young woman caught in the crossfire and left to fester in the limelight.

Sound familiar? Since the case broke, transatlantic front pages have been haunted by the ‘temptresses’ of powerful male figures. Thirty-three years after the Profumo Affair, Monica Lewinsky, who was only 22 when her affair with then-president Bill Clinton was exposed, was mocked as a slut, a tramp, and – most notoriously – “that woman”.

Ashley Dupré remains known as the 22-year-old “hooker who ended Eliot Spitzer’s career in politics” after sleeping with the governor of New York in 2008. Meanwhile, only last year, British journalists slobbered over lingerie-clad, pole-dancing photos of Jennifer Arcuri after rumours that she’d had a relationship with Boris Johnson.

The meaning behind such coverage is indisputable: the only agency afforded to “that” sort of woman is that of her sexuality. By daring to screw her way above her station, she deserves to be branded, vilified, flogged on public display.

“Tabloid headlines and clickbait have reduced women to an almost biblical stereotype, undeserving of dignity should they err”

Yet, the conscience of modern media is tainted by more female victims than these. ‘People’s Princess’ Diana Spencer was the darling of British royal coverage before her death in 1997. To this day, the media’s role in that car accident remains under scrutiny over questions of whether they physically hounded her to her death. In light of tabloid criticism of Meghan Markle, Diana’s treatment has been raised again, with George Clooney warning last year: “[Meghan] is being pursued and vilified and chased in the same way that Diana was. It’s history repeating itself.”

Now, of course, Caroline Flack’s suicide has brought media scrutiny to boiling point. To date, over 860,000 people have signed a petition to introduce Caroline’s Law: a bill that would make it a criminal offence “to knowingly and relentlessly bully a person, whether they be in the public eye or not, up to the point that they take their own life”. It’s ironic that The Trial of Christine Keeler was televised the same month as Flack’s first appearance in court for domestic abuse; the footage of a nervous young woman swamped by cameramen was strikingly similar.

Regardless of whether Flack was innocent or guilty of assaulting her boyfriend, the media’s treatment of her is evocative of the sexist and potentially destructive standards women are held to: standards that have clearly festered for over half a century. Snappy tabloid headlines and, in this digital age, clickbait have reduced women to an almost biblical stereotype, undeserving of dignity should they err.

Keeler’s and Flack’s cases are hardly similar, but in the eyes of the media, little, it seems, has changed. Both – like so many women in between – bore the brunt of an aggressive media climate in which they, their pain, and the nuance of their experiences were reduced to little more than commodities. Writing of her love life post-Profumo, Keeler remarked: “I was a trophy to boast to the boys about, but not to take home to Mummy.” However, the metaphor surpasses the bedroom. Both in 1963 and the years afterwards, it was not only Keeler’s body that became the objectified “trophy”, but her story too. The “boys”, the male gaze, defined it. The destruction that wreaked upon her reputation was one thing; the destruction it’s wreaked on other women since is another.

The Trial of Christine Keeler may have been praised by contemporary audiences, but the issues it raises remain prevalent. Post-#MeToo, we may be willing to address the sexual politics that engulfed her, but that is not to say we have re-painted the entire canvas. The cries against Christine Keeler projected far beyond the bedroom, and continue to echo today.